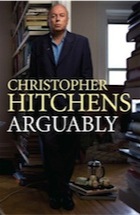

Over the past decade Hitchens has taken a combative stance on world events. He reflects on these writings

Tunisian protesters with a picture of Mohamed Bouazizi, who 'set himself alight ... in protest at just one too many humiliations'. Photograph: Zohra Bensemra/Reuters

Three men: Mohamed Bouazizi, Abu-Abdel Monaam Hamedeh, and Ali Mehdi Zeu – a Tunisian street vendor, an Egyptian restaurateur and a Libyan husband and father. In the spring of 2011, the first of them set himself alight in the town of Sidi Bouzid, in protest at just one too many humiliations at the hands of petty officialdom. The second also took his own life as Egyptians began to rebel en masse at the stagnation and meaninglessness of Mubarak's Egypt. The third, it might be said, gave his life as well as took it: loading up his modest car with petrol and home-made explosives and blasting open the gate of the Katiba barracks in Benghazi – symbolic Bastille of the detested and demented Gaddafi regime in Libya.

Three men: Mohamed Bouazizi, Abu-Abdel Monaam Hamedeh, and Ali Mehdi Zeu – a Tunisian street vendor, an Egyptian restaurateur and a Libyan husband and father. In the spring of 2011, the first of them set himself alight in the town of Sidi Bouzid, in protest at just one too many humiliations at the hands of petty officialdom. The second also took his own life as Egyptians began to rebel en masse at the stagnation and meaninglessness of Mubarak's Egypt. The third, it might be said, gave his life as well as took it: loading up his modest car with petrol and home-made explosives and blasting open the gate of the Katiba barracks in Benghazi – symbolic Bastille of the detested and demented Gaddafi regime in Libya.In the long human struggle, the idea of "martyrdom" presents itself with a Janus-like face. Those willing to die for a cause larger than themselves have been honoured from the Periclean funeral oration to the Gettysburg Address. Viewed more sceptically, those with a zeal to die have sometimes been suspect for excessive enthusiasm and self-righteousness; even fanaticism. The anthem of my old party, the British Labour party, speaks passionately of a flag that is deepest red, and which has "shrouded oft our martyred dead". Underneath my college windows at Oxford stood – stands – the memorial to the "Oxford Martyrs", Bishops Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley, who were burned alive for Protestant heresies by the Catholic Queen Mary in October 1555. "The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church," wrote the church father Tertullian in late first-century Carthage, and the association of the martyr with blind faith has been consistent down the centuries, with the faction being burned often waiting for its own turn to do the burning. I think the Labour party can be acquitted on that charge. So can Jan Palach, the young Czech student who immolated himself in Wenceslas Square in January 1969 in protest against the Soviet occupation of his country. I helped to organise a rally at the Oxford Memorial in his honour, and later became associated with the Palach Press, a centre of exile dissent and publication which was a contributor, two decades later, to the "Velvet Revolution" of 1989. This was a completely secular and civil initiative, which never caused a drop of human blood to be spilled.

Full piece at The Guardian.

No comments:

Post a Comment