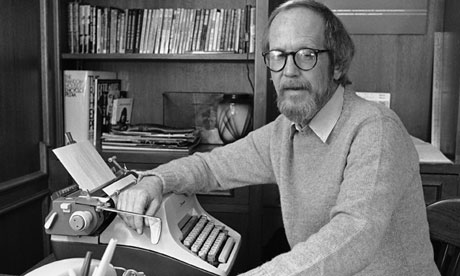

Elmore Leonard in 1983. 'Don't say what you see; don't describe what's obvious,' was the mantra he followed when writing his books. Photograph: Rob Kozloff/AP

When Elmore Leonard's Stick was published in Britain in 1984, one newspaper called it "a fine first novel". At almost 60, the author would have been amused at such an accolade; it was, in fact, his 21st novel, and Leonard, who has died aged 87, had been selling his fiction regularly, occasionally to Hollywood. But the genres in which he chose to work often failed to attract serious critical attention: westerns first, then crime novels set in the contemporary urban hinterlands.

Westerns as a literary genre still lack respectability, but the craft and energy of Leonard's crime novels, which include Get Shorty, Out of Sight and LaBrava, eventually made them impossible to ignore. Still, recognition came late: only in 1992 did the Mystery Writers of America grant him its highest accolade, the Grand Master Edgar. In 2009, his lifetime achievements were recognised by both the Western Writers of America and PEN USA. By then, Leonard's appeal went far beyond generic boundaries. In 1998, Martin Amis, in the course of a somewhat idolatrous interview with Leonard at the Writers' Guild in Beverly Hills, declared him "as close as anything you have here in America to a national novelist". He also revealed that Saul Bellow had Leonard's work on his bookshelves.

Leonard was born in New Orleans. His father was a General Motors executive whose job entailed a nomadic existence. The family spent the first 10 years of Elmore's life travelling the American south and he retained traces of a southern drawl. After second world war service in the US naval reserve, he graduated with an English degree from the University of Detroit. For 11 years, from 1950, he was employed as a copywriter for a Detroit agency, mostly writing car ads. Interviewed years later, he pronounced adverbs in fiction "a moral sin: I used up all my adverbs when I was writing car catalogues for Chevrolet". Getting up at five every morning and writing fiction for two hours before going to work, he maintained a decent output without relying on it for an income.

After he left the agency, he spent several years providing scripts for educational films, including for Encyclopaedia Britannica films. Here, too, he learned something that stayed with him: "Don't say what you see; don't describe what's obvious." That apparent detachment from an authorial point of view was one of the distinguishing characteristics of his fiction. "I don't want you to be aware of me in my books. I'm not ever telling the story. When you're reading a novel, you don't want people telling you things, you want to see it, to hear it."

More

Westerns as a literary genre still lack respectability, but the craft and energy of Leonard's crime novels, which include Get Shorty, Out of Sight and LaBrava, eventually made them impossible to ignore. Still, recognition came late: only in 1992 did the Mystery Writers of America grant him its highest accolade, the Grand Master Edgar. In 2009, his lifetime achievements were recognised by both the Western Writers of America and PEN USA. By then, Leonard's appeal went far beyond generic boundaries. In 1998, Martin Amis, in the course of a somewhat idolatrous interview with Leonard at the Writers' Guild in Beverly Hills, declared him "as close as anything you have here in America to a national novelist". He also revealed that Saul Bellow had Leonard's work on his bookshelves.

Leonard was born in New Orleans. His father was a General Motors executive whose job entailed a nomadic existence. The family spent the first 10 years of Elmore's life travelling the American south and he retained traces of a southern drawl. After second world war service in the US naval reserve, he graduated with an English degree from the University of Detroit. For 11 years, from 1950, he was employed as a copywriter for a Detroit agency, mostly writing car ads. Interviewed years later, he pronounced adverbs in fiction "a moral sin: I used up all my adverbs when I was writing car catalogues for Chevrolet". Getting up at five every morning and writing fiction for two hours before going to work, he maintained a decent output without relying on it for an income.

After he left the agency, he spent several years providing scripts for educational films, including for Encyclopaedia Britannica films. Here, too, he learned something that stayed with him: "Don't say what you see; don't describe what's obvious." That apparent detachment from an authorial point of view was one of the distinguishing characteristics of his fiction. "I don't want you to be aware of me in my books. I'm not ever telling the story. When you're reading a novel, you don't want people telling you things, you want to see it, to hear it."

More

No comments:

Post a Comment