To peg out, cash in one's chips or succumb? The lexicon of dying is remarkably inventive

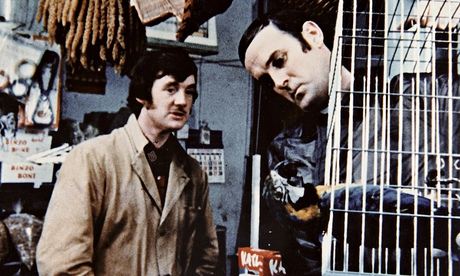

A profusion of defunctive synonymy … Monty Python’s ‘Dead Parrot’ sketch. Photograph: Allstar

How would you like to die, linguistically? When the lexicographers were compiling their citations for the Oxford English Dictionary, they came across this remarkable one, in a US graveyard:

It's the earliest recorded use of pass out meaning to die. The usage continued into the 20th century, but I doubt that it would be used now. Today we associate passing out with excessive tiredness, drugs, or drink. I don't want to be passed out on my gravestone.

Caroline, wife of EJ Langston, born on March 23 1833. Passed out Dec 18 1867

It's the earliest recorded use of pass out meaning to die. The usage continued into the 20th century, but I doubt that it would be used now. Today we associate passing out with excessive tiredness, drugs, or drink. I don't want to be passed out on my gravestone.

A remarkable creativity surrounds the vocabulary of death. The words and expressions range from the solemn and dignified to the jocular and mischievous, and they reflect the changing ways we have thought about life and death over the centuries. The early verbs are rather mundane and encompass literal notions of "leaving", such as wend, go out of this world, fare, leave and part. Only later do we get a sense of where one is going to, with an initial focus on ancestors evolving into the notion of a divine presence: be gathered to one's fathers, go over to the majority, go home, pass to one's reward, launch into eternity, go to glory, meet one's Maker, get one's call.

The list of verbs for dying in the Historical Thesaurus displays a remarkable inventiveness, as people struggled to find fresh forms of expression. The language of death is inevitably euphemistic, but few of the verbs or idioms are elaborate or opaque. In fact, the history of verbs for dying displays a real simplicity: most consist of only one syllable. Even the euphemisms of later centuries have a markedly succinct character (slip one's cable, kick the bucket). More

No comments:

Post a Comment