Does handwriting have a value that email and texting can't replace? In this extract from his new book, The Missing Ink, Philip Hensher laments the slow death of the written word, and explains how putting pen to paper can still occupy a special place in our lives

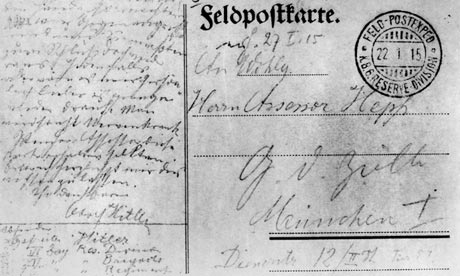

A postcard written by Hitler in January 1915. His writing style indicates his megalomaniacal psychopathy, say graphologists. Photograph: The Granger Collection / TopFoto

About six months ago, I realised that I had no idea what the handwriting of a good friend of mine looked like. I had known him for over a decade, but somehow we had never communicated using handwritten notes. He had left voice messages for me, emailed me, sent text messages galore. But I don't think I had ever had a letter from him written by hand, a postcard from his holidays, a reminder of something pushed through my letter box. I had no idea whether his handwriting was bold or crabbed, sloping or upright, italic or rounded, elegant or slapdash.

It hit me that we are at a moment when handwriting seems to be about to vanish from our lives altogether. At some point in recent years, it has stopped being a necessary and inevitable intermediary between people – a means by which individuals communicate with each other, putting a little bit of their personality into the form of their message as they press the ink-bearing point on to the paper. It has started to become just one of many options, and often an unattractive, elaborate one.

For each of us, the act of putting marks on paper with ink goes back as far as we can probably remember. At some point, somebody comes along and tells us that if you make a rounded shape and then join it to a straight vertical line, that means the letter "a", just like the ones you see in the book. (But the ones in the book have a little umbrella over the top, don't they? Never mind that, for the moment: this is how we make them for ourselves.) If you make a different rounded shape, in the opposite direction, and a taller vertical line, then that means the letter "b". Do you see? And then a rounded shape, in the same direction as the first letter, but not joined to anything – that makes a "c". And off you go.

For each of us, the act of putting marks on paper with ink goes back as far as we can probably remember. At some point, somebody comes along and tells us that if you make a rounded shape and then join it to a straight vertical line, that means the letter "a", just like the ones you see in the book. (But the ones in the book have a little umbrella over the top, don't they? Never mind that, for the moment: this is how we make them for ourselves.) If you make a different rounded shape, in the opposite direction, and a taller vertical line, then that means the letter "b". Do you see? And then a rounded shape, in the same direction as the first letter, but not joined to anything – that makes a "c". And off you go.

Actually, I don't think I have any memory of this initial introduction to the art of writing letters on paper. Our handwriting, like ourselves, seems always to have been there.

Full piece at The Observer

It hit me that we are at a moment when handwriting seems to be about to vanish from our lives altogether. At some point in recent years, it has stopped being a necessary and inevitable intermediary between people – a means by which individuals communicate with each other, putting a little bit of their personality into the form of their message as they press the ink-bearing point on to the paper. It has started to become just one of many options, and often an unattractive, elaborate one.

For each of us, the act of putting marks on paper with ink goes back as far as we can probably remember. At some point, somebody comes along and tells us that if you make a rounded shape and then join it to a straight vertical line, that means the letter "a", just like the ones you see in the book. (But the ones in the book have a little umbrella over the top, don't they? Never mind that, for the moment: this is how we make them for ourselves.) If you make a different rounded shape, in the opposite direction, and a taller vertical line, then that means the letter "b". Do you see? And then a rounded shape, in the same direction as the first letter, but not joined to anything – that makes a "c". And off you go.

For each of us, the act of putting marks on paper with ink goes back as far as we can probably remember. At some point, somebody comes along and tells us that if you make a rounded shape and then join it to a straight vertical line, that means the letter "a", just like the ones you see in the book. (But the ones in the book have a little umbrella over the top, don't they? Never mind that, for the moment: this is how we make them for ourselves.) If you make a different rounded shape, in the opposite direction, and a taller vertical line, then that means the letter "b". Do you see? And then a rounded shape, in the same direction as the first letter, but not joined to anything – that makes a "c". And off you go.Actually, I don't think I have any memory of this initial introduction to the art of writing letters on paper. Our handwriting, like ourselves, seems always to have been there.

Full piece at The Observer

No comments:

Post a Comment