Themes of fate, family life and renewal are brilliantly explored in this story of a life lived in wartime Britain

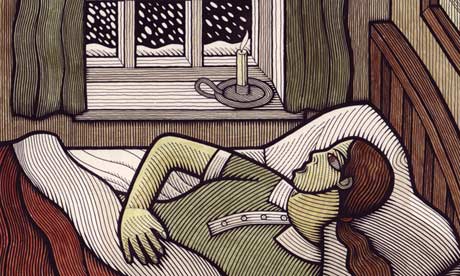

Fairytale atmosphere … Sylvie Todd is cut

off from outside help by the encroaching snow while giving birth to her third

child. Illustration: Clifford Harper/Agraphia.co.uk

Kate Atkinson's new novel is a marvel, a great big confidence trick – but one

that invites the reader to take part in the deception. In fact, it is impossible

to ignore it. Every time you attempt to lose yourself in the story of Ursula

Todd, a child born in affluent and comparatively happy circumstances on 11

February 1910, it simply stops. If this sounds like the quick route to a short

book, don't worry: the narrative starts again – and again and again – but each

time it takes a different course, its details sometimes radically, sometimes

marginally altered, its outcome utterly unpredictable. Atkinson's general rule

is that things seem to get better with repetition, but this, her

self-undermining novel seems to warn us, is a comfort that is by no means

guaranteed, either.

She begins as she means to go on, and at the very beginning. (In fact, even

this is not quite true: a brief prologue shows us Ursula in a Munich coffee shop

in 1930, assassinating Hitler with her father's old service revolver.) At the

start of the novel "proper", Sylvie Todd is giving birth to her third child, her

situation given a fairytale atmosphere by the encroaching snow which also, alas,

cuts her off from outside help in the form of Dr Fellowes or Mrs Haddock, the

midwife. Ursula is stillborn, with the umbilical cord wrapped around her neck,

her life unsaved for want of a pair of surgical scissors. Fortunately, though,

she is allowed another go at the business of coming into being; in take two, Dr

Fellowes makes it, cuts the cord and proceeds to his reward of a cold collation

and some homemade piccalilli (it might be too fanciful to notice that even the

piccalilli repeats).

She begins as she means to go on, and at the very beginning. (In fact, even

this is not quite true: a brief prologue shows us Ursula in a Munich coffee shop

in 1930, assassinating Hitler with her father's old service revolver.) At the

start of the novel "proper", Sylvie Todd is giving birth to her third child, her

situation given a fairytale atmosphere by the encroaching snow which also, alas,

cuts her off from outside help in the form of Dr Fellowes or Mrs Haddock, the

midwife. Ursula is stillborn, with the umbilical cord wrapped around her neck,

her life unsaved for want of a pair of surgical scissors. Fortunately, though,

she is allowed another go at the business of coming into being; in take two, Dr

Fellowes makes it, cuts the cord and proceeds to his reward of a cold collation

and some homemade piccalilli (it might be too fanciful to notice that even the

piccalilli repeats).

Ursula's childhood is to be punctuated with such near-misses: the treacherous undertow of the Cornish sea, icy tiles during a rooftop escapade, the wildfire spread of Spanish flu. Each disaster is confirmed by variations on the phrase "darkness fell", and each new beginning heralded by the tabula rasa that snow brings. Ursula carries within her a vague, dimly apprehended sense of other, semi-lived lives, inexpressible except as impetuous actions – such as when she pushes a housemaid down the stairs to save her from a more terrible ending. That misdemeanour lands her in the office of a psychiatrist who introduces her, in kindly fashion, to the concept of reincarnation and to the roughly opposing theory of amor fati, particularly as espoused by Nietzsche: the acceptance, or even embrace, of one's fate, and the rejection of the idea that anything could, or should, have unfolded differently.

Full review

Earlier review by Nicky Pellegrino

She begins as she means to go on, and at the very beginning. (In fact, even

this is not quite true: a brief prologue shows us Ursula in a Munich coffee shop

in 1930, assassinating Hitler with her father's old service revolver.) At the

start of the novel "proper", Sylvie Todd is giving birth to her third child, her

situation given a fairytale atmosphere by the encroaching snow which also, alas,

cuts her off from outside help in the form of Dr Fellowes or Mrs Haddock, the

midwife. Ursula is stillborn, with the umbilical cord wrapped around her neck,

her life unsaved for want of a pair of surgical scissors. Fortunately, though,

she is allowed another go at the business of coming into being; in take two, Dr

Fellowes makes it, cuts the cord and proceeds to his reward of a cold collation

and some homemade piccalilli (it might be too fanciful to notice that even the

piccalilli repeats).

She begins as she means to go on, and at the very beginning. (In fact, even

this is not quite true: a brief prologue shows us Ursula in a Munich coffee shop

in 1930, assassinating Hitler with her father's old service revolver.) At the

start of the novel "proper", Sylvie Todd is giving birth to her third child, her

situation given a fairytale atmosphere by the encroaching snow which also, alas,

cuts her off from outside help in the form of Dr Fellowes or Mrs Haddock, the

midwife. Ursula is stillborn, with the umbilical cord wrapped around her neck,

her life unsaved for want of a pair of surgical scissors. Fortunately, though,

she is allowed another go at the business of coming into being; in take two, Dr

Fellowes makes it, cuts the cord and proceeds to his reward of a cold collation

and some homemade piccalilli (it might be too fanciful to notice that even the

piccalilli repeats).Ursula's childhood is to be punctuated with such near-misses: the treacherous undertow of the Cornish sea, icy tiles during a rooftop escapade, the wildfire spread of Spanish flu. Each disaster is confirmed by variations on the phrase "darkness fell", and each new beginning heralded by the tabula rasa that snow brings. Ursula carries within her a vague, dimly apprehended sense of other, semi-lived lives, inexpressible except as impetuous actions – such as when she pushes a housemaid down the stairs to save her from a more terrible ending. That misdemeanour lands her in the office of a psychiatrist who introduces her, in kindly fashion, to the concept of reincarnation and to the roughly opposing theory of amor fati, particularly as espoused by Nietzsche: the acceptance, or even embrace, of one's fate, and the rejection of the idea that anything could, or should, have unfolded differently.

Full review

Earlier review by Nicky Pellegrino

No comments:

Post a Comment