All hail the 'bookeen', a new format that's perfect for short stories, novellas and essays

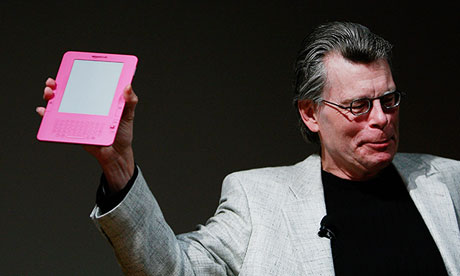

Stephen King holds aloft a special pink Kindle given to him by Amazon's CEO, Jeff Bezos. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty Images

New formats in literature are rare, and disruptive. They usually accompany a change in technology. Amazon was the first big player to realise that digitisation would allow for a new literary format. In January 2011, it quietly launched a substore on its US website to sell something it called a Kindle Single: Compelling Ideas Expressed At Their Natural Length, as a press release headline blandly put it.

"Typically between 5,000 and 30,000 words, Kindle Singles are editorially curated and showcase writing from both new and established voices – from bestselling novelists and journalists to previously unpublished writers."

Those lines may not sound like a call to revolution. But they are. Writers can seldom express ideas "at their natural length", because in the world of traditional print only a few lengths are commercially viable. Write too long, and you'll be told to cut it (as Stephen King was when The Stand came in too long to be bound in paperback). Worse, write too short, and you won't get published at all. Your perfect story is 50 pages long – or 70, or 100? Good luck getting that printed anywhere.

Hence the revolution. Because the new length exploits this hole in traditional publishing.

The hole has existed for 500 years; it's baked into the print model. The high fixed overheads of book production – printing, binding, warehousing and distributing a labour-intensive physical object – have tended to make books of fewer than 100 pages too expensive for the customer. (And print magazines and newspapers can take works of only 10, maybe 15 pages, max.)

But although commercial print publishers have never liked novellas or novelettes, authors always have. Indeed, many writers have done their best work at that length, despite the difficulty of finding publication (Melville's Bartleby, the Scrivener; Kafka's The Metamorphosis). However brilliantly written, though, they have often been disrespectfully published, awkwardly bundled up with other stories to pad out a commercially viable print book.

More

"Typically between 5,000 and 30,000 words, Kindle Singles are editorially curated and showcase writing from both new and established voices – from bestselling novelists and journalists to previously unpublished writers."

Those lines may not sound like a call to revolution. But they are. Writers can seldom express ideas "at their natural length", because in the world of traditional print only a few lengths are commercially viable. Write too long, and you'll be told to cut it (as Stephen King was when The Stand came in too long to be bound in paperback). Worse, write too short, and you won't get published at all. Your perfect story is 50 pages long – or 70, or 100? Good luck getting that printed anywhere.

Hence the revolution. Because the new length exploits this hole in traditional publishing.

The hole has existed for 500 years; it's baked into the print model. The high fixed overheads of book production – printing, binding, warehousing and distributing a labour-intensive physical object – have tended to make books of fewer than 100 pages too expensive for the customer. (And print magazines and newspapers can take works of only 10, maybe 15 pages, max.)

But although commercial print publishers have never liked novellas or novelettes, authors always have. Indeed, many writers have done their best work at that length, despite the difficulty of finding publication (Melville's Bartleby, the Scrivener; Kafka's The Metamorphosis). However brilliantly written, though, they have often been disrespectfully published, awkwardly bundled up with other stories to pad out a commercially viable print book.

More

No comments:

Post a Comment