The history of publishing is packed with pioneering entrepreneurs who would have revelled in the opportunities of the digital revolution

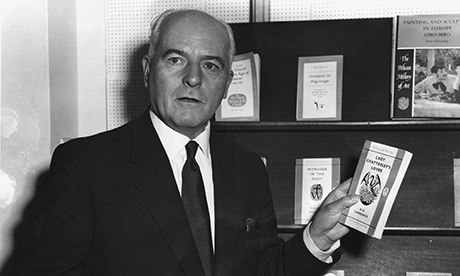

Eureka moment … Allen Lane, founder of Penguin publishers, holding a copy of Lady Chatterley's Lover. Photograph: Hulton Getty

These are disturbing times for booksellers, publishers and writers. The last 20 years have seen a transformation in the world of letters unequalled since the days of William Caxton. In 1993, we were in limbo between hot metal and cool word processing. Neither Amazon nor Google had been invented. The ebook was for science fiction. Today, however, the world of books has become a kind of IT laboratory. On this new frontier, publishers face a future whose shape is a mystery. In a confusing present, traditionally, it's the past that can often supply a quantum of solace. I've just completed a Radio 4 series about five great independent publishers – John Murray, Macmillan, Penguin, Weidenfeld and Faber – and have discovered in the stories of the Victorian and 20th-century book world some intriguing clues to the future prospects for editing and writing.

Probably the most prominent ogre in the contemporary book trade is Amazon. By one crude analysis, the recent Penguin-Random House merger is a defensive alliance motivated by "the threat of Amazon". However, for an 18th-century bookseller, say John Murray, whose imprint came to publish Byron, Austen and Darwin, the service offered by Amazon could seem a natural progression – state-of-the-art book distribution. The "threat" comes from Amazon's intentions, its extraordinary grip on the market share of the big conglomerates.

The first John Murray's answer to the book-selling trade wars of late 18th‑century London was simple: he quit the shop floor and became a publisher – just as Amazon has begun to explore the possibilities of publishing. Murray was an innovative entrepreneur, but he was typical of his trade. He was a Tory (in stark contrast to the Whig radicalism of his fiery poet Lord Byron) and the British book trade has always been inherently conservative. Its grandees tend to resist change. Usually, it has been maverick outsiders whose impact on the book world has been the most profound.

Allen Lane, the publisher who created Penguin and became the father of the paperback revolution, was another classic outsider. Born in Bristol in 1902, he left school at 16 and learned the book business on the shop floor, stacking shelves. In the 1920s, Lane was among the first to understand that the impact of the first world war, successive education acts and votes for women had created a potentially huge mass market for cheap books in soft covers. But it wasn't until he took a frustrating train journey to the West Country to stay with his friend, the young crime writer Agatha Christie, that he stumbled on his opportunity.

The story goes that, waiting for his connection at Exeter, Lane could find nothing worth reading on the station bookstall – still an all-too familiar experience. Whereupon Allen Lane had his eureka moment: inexpensive books, in paper covers, at sixpence apiece – the price of a packet of cigarettes. Cheap, attractive paperback editions for a new generation of readers. Bingo! The old guard in London's clubland was horrified. "Far too risky. Far too popular. This fellow threatens the heart and soul of the hardback business." But Lane forged ahead. In 1935 he set up Penguin to produce nothing but paperbacks. He also pioneered the idea of a brand. A uniform type-face. Those famous colour codes: orange for fiction, green for crime, and black for classics. Lane's brainwave was the biggest single book innovation of the 20th century, and in its day the equal of the ebook. For a while, his idea dominated the market. Households across Britain began sprouting those colour-coded spines. A format that at the outset seemed to threaten vested interests became an object of veneration.

Another timely lesson from the Penguin story is Lane's confidence in the taste of the ordinary reader. It has become commonplace, in culturally nervous times, to disparage the mass market. See, for instance, virtually any review of Dan Brown's Inferno or the critical indifference shown towards a popular writer such as Bernard Cornwell.

More

Probably the most prominent ogre in the contemporary book trade is Amazon. By one crude analysis, the recent Penguin-Random House merger is a defensive alliance motivated by "the threat of Amazon". However, for an 18th-century bookseller, say John Murray, whose imprint came to publish Byron, Austen and Darwin, the service offered by Amazon could seem a natural progression – state-of-the-art book distribution. The "threat" comes from Amazon's intentions, its extraordinary grip on the market share of the big conglomerates.

The first John Murray's answer to the book-selling trade wars of late 18th‑century London was simple: he quit the shop floor and became a publisher – just as Amazon has begun to explore the possibilities of publishing. Murray was an innovative entrepreneur, but he was typical of his trade. He was a Tory (in stark contrast to the Whig radicalism of his fiery poet Lord Byron) and the British book trade has always been inherently conservative. Its grandees tend to resist change. Usually, it has been maverick outsiders whose impact on the book world has been the most profound.

Allen Lane, the publisher who created Penguin and became the father of the paperback revolution, was another classic outsider. Born in Bristol in 1902, he left school at 16 and learned the book business on the shop floor, stacking shelves. In the 1920s, Lane was among the first to understand that the impact of the first world war, successive education acts and votes for women had created a potentially huge mass market for cheap books in soft covers. But it wasn't until he took a frustrating train journey to the West Country to stay with his friend, the young crime writer Agatha Christie, that he stumbled on his opportunity.

The story goes that, waiting for his connection at Exeter, Lane could find nothing worth reading on the station bookstall – still an all-too familiar experience. Whereupon Allen Lane had his eureka moment: inexpensive books, in paper covers, at sixpence apiece – the price of a packet of cigarettes. Cheap, attractive paperback editions for a new generation of readers. Bingo! The old guard in London's clubland was horrified. "Far too risky. Far too popular. This fellow threatens the heart and soul of the hardback business." But Lane forged ahead. In 1935 he set up Penguin to produce nothing but paperbacks. He also pioneered the idea of a brand. A uniform type-face. Those famous colour codes: orange for fiction, green for crime, and black for classics. Lane's brainwave was the biggest single book innovation of the 20th century, and in its day the equal of the ebook. For a while, his idea dominated the market. Households across Britain began sprouting those colour-coded spines. A format that at the outset seemed to threaten vested interests became an object of veneration.

Another timely lesson from the Penguin story is Lane's confidence in the taste of the ordinary reader. It has become commonplace, in culturally nervous times, to disparage the mass market. See, for instance, virtually any review of Dan Brown's Inferno or the critical indifference shown towards a popular writer such as Bernard Cornwell.

More

No comments:

Post a Comment