The great Bengali thinker Rabindranath Tagore, born 150 years ago, was a passionate political author. Sadly, literary writers today seem to have no time for politics

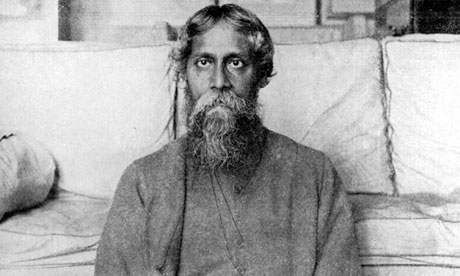

Rabindranath Tagore: an exceptional figure – and the first Asian recipient of a Nobel prize for literature. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The past sometimes shames us. At least, visitors this weekend to Dartington Hall in the south Devon town of Totnes must have come away feeling taunted by history. Because while the festival they attended was celebrating the life of Rabindranath Tagore, the great Bengali artist and thinker born 150 years ago, it also cast a shard of light on a gaping, and usually unremarked upon, hole in today's culture. You glimpsed it every time a musician performed one of Tagore's songs urging fellow Indians not to give up their struggle against British rule, and you confronted it directly in discussions of the poet's political and social campaigning. Because what his legacy draws attention to is a creature so rare in today's culture as to be semi-endangered: the political author.

Even the most casual acquaintance with Tagore's work cannot escape his politics. His novels attacked the oppression of women; his essays warned about environmental degradation; he argued with Gandhi about what an independent India should look like; and he delivered lectures in America on the evils of nationalism ("at $700 per scold", as one newspaper sniped). Nor was the poet all talk: a believer in educational reform, he established a school, then a university in the Bengali countryside. They have grown vastly since, although students reportedly still take their lessons sat under trees. Even the venue for this weekend's festival, Dartington Hall, was a 500-year old wreck – until a couple of western Tagoreans bought it and, at his urging, transformed it into a centre for learning and agricultural work and to reinvigorate an impoverished rural community.

The first Asian recipient of a Nobel prize for literature, Tagore was an exceptional figure – but he was not alone. Another Bengali, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, won huge success for his stories criticising India's caste and class system; while Mulk Raj Anand published novels titled Untouchable and Coolie. As for Tagore's western contemporaries, they were just as engaged with their politics and society. Spanish civil-war combatant Orwell is the most striking example, but there was also Spender, Auden and Pound.

Look for their equivalents in England or America now, and you'll be disappointed. Some politically committed authors immediately come to mind, such as Dave Eggers – for his novels on Sudanese refugees and post-Katrina New Orleans, and his establishment of children's reading groups – but the paucity of their number reinforces how few there are. India is subject to a similar lack: Arundhati Roy is the stand-out example of the author-turned-activist, but the fact that she has not written a novel after 1997's The God of Small Things suggests that she has traded fiction for campaigning.

Full story at The Guardian.

Even the most casual acquaintance with Tagore's work cannot escape his politics. His novels attacked the oppression of women; his essays warned about environmental degradation; he argued with Gandhi about what an independent India should look like; and he delivered lectures in America on the evils of nationalism ("at $700 per scold", as one newspaper sniped). Nor was the poet all talk: a believer in educational reform, he established a school, then a university in the Bengali countryside. They have grown vastly since, although students reportedly still take their lessons sat under trees. Even the venue for this weekend's festival, Dartington Hall, was a 500-year old wreck – until a couple of western Tagoreans bought it and, at his urging, transformed it into a centre for learning and agricultural work and to reinvigorate an impoverished rural community.

The first Asian recipient of a Nobel prize for literature, Tagore was an exceptional figure – but he was not alone. Another Bengali, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, won huge success for his stories criticising India's caste and class system; while Mulk Raj Anand published novels titled Untouchable and Coolie. As for Tagore's western contemporaries, they were just as engaged with their politics and society. Spanish civil-war combatant Orwell is the most striking example, but there was also Spender, Auden and Pound.

Look for their equivalents in England or America now, and you'll be disappointed. Some politically committed authors immediately come to mind, such as Dave Eggers – for his novels on Sudanese refugees and post-Katrina New Orleans, and his establishment of children's reading groups – but the paucity of their number reinforces how few there are. India is subject to a similar lack: Arundhati Roy is the stand-out example of the author-turned-activist, but the fact that she has not written a novel after 1997's The God of Small Things suggests that she has traded fiction for campaigning.

Full story at The Guardian.

No comments:

Post a Comment