From Pamela to Bridget Jones, fictional diaries enthral us. What is it that so appeals both to writers and their readers?

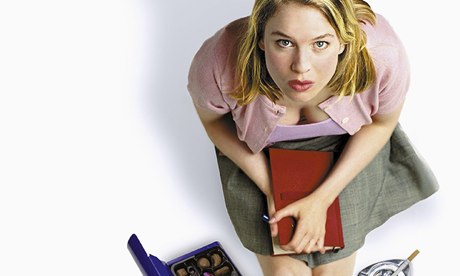

A first-person narrative that keeps the narrator in suspense … Helen Fielding's Bridget Jones is part of a rich tradition. Photograph: Working Title/Sportsphoto Ltd/Allstar

Diaries: you get one as a Christmas present, start writing it, and continue for, oh, a few days more or less than you go to the gym for the new year. Then you give it up, along with that new dietary regime.

Fictional characters, however – forced by their authors to carry the story, slaves to the process of narrative – tend to be much more reliable. And there's good reason for the format's popularity in novels. At the most basic level, it means you can have a first-person narration without the protagonist knowing what's going to happen (although going out on a dangerous adventure is slightly less exciting, because the diarist definitely got back safely to write it up).

Fictional diaries have been amusing and entertaining us since the modern novel's early days. Here are some favourite examples.

More

Fictional characters, however – forced by their authors to carry the story, slaves to the process of narrative – tend to be much more reliable. And there's good reason for the format's popularity in novels. At the most basic level, it means you can have a first-person narration without the protagonist knowing what's going to happen (although going out on a dangerous adventure is slightly less exciting, because the diarist definitely got back safely to write it up).

Fictional diaries have been amusing and entertaining us since the modern novel's early days. Here are some favourite examples.

Pamela

Samuel Richardson's Pamela (1740) is usually described as an epistolary novel. But our heroine also writes a journal, and then sews it into her underwear for secrecy (she describes it as "in my undercoat, next my linen"), so she is wearing it at all times. It is hard to imagine a better metaphor for the history of women and their writing – and, perhaps, women's diaries – over the past 250 years.Wuthering Heights

It's easily forgotten, but Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Brontë has a skeletal framework of a diary: "I have just returned from a visit to my landlord … Yesterday afternoon set in misty and cold". Mr Lockwood will learn about true emotion day by day as he finds out and writes down the story of Heathcliff and the Earnshaws.What Katy Did

Susan Coolidge's 1872 book What Katy Did, beloved by generations of children, contains a scene where the older siblings laugh at young Dorry's diary, with its repeated entry: "Forgit what did." Many of us could empathise with that, though we can't hope to inspire, of all unlikely things, a Philip Larkin poem about unkept diaries called Forget What Did, the title taken from Dorry.More

No comments:

Post a Comment