Colm Tóibín talks about writing a Broadway show, giving up poetry at 20 – and why writers would be good at running military campaigns

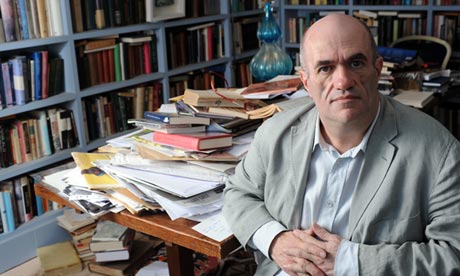

Writing tends to be very deliberate … Colm

Tóibín. Photograph: Kim Haughton

What first drew you to writing?

When I was 12, it was agreed I would spend some hours studying every evening. I discovered rhyme and began to write poetry. I did this until I was 20, when I realised the poems were no good.

What was your big breakthrough?

Suffering is too strong a word, but writing is serious work. I pull the stuff up from me – it's not as if it's a pleasure.

What's more important in fiction: story or style?

You're often wrong. I work very deliberately, with a plan. But sometimes I come to a point that I planned as the end and it needs softening. Ending a novel is almost like putting a child to sleep – it can't be done abruptly.

Do you read your reviews?

Finish everything you start. Often, you don't know where you're going for a while; then halfway through, something comes and you know. If you abandon things, you never find that out.

What work of art would you most like to own?

That there's any wildness attached to it. Writing tends to be very deliberate. A novelist could probably run a military campaign with some success. They could certainly run a country.

What are you writing now?

I'm close to finishing a novel. And I have a play [an adaptation of The Testament of Mary] opening on Broadway in about a month. There's a daily phone call from someone saying: "If we cut this sentence, would it break your heart?" Most of the time, I'm very good and say it wouldn't.

What's your greatest ambition?

To write better.

When I was 12, it was agreed I would spend some hours studying every evening. I discovered rhyme and began to write poetry. I did this until I was 20, when I realised the poems were no good.

What was your big breakthrough?

When Serpent's Tail agreed

to publish my first novel, The South. I'd

just spent a year in Barcelona and got the news on my way home. After landing in

Dublin, I sat alone in the airport bar for an hour, just trying to take it

in.

Do you suffer for your art?Suffering is too strong a word, but writing is serious work. I pull the stuff up from me – it's not as if it's a pleasure.

What's more important in fiction: story or style?

I'm against story. I

remember [the painter] Howard

Hodgkin really disliking being called a colourist. People love talking about

writers as storytellers, but I hate being called that: it suggests I got it from

my grandmother or something, when my writing really comes out of silence. If a

storyteller came up to me, I'd run away.

How do you know when a book is finished?You're often wrong. I work very deliberately, with a plan. But sometimes I come to a point that I planned as the end and it needs softening. Ending a novel is almost like putting a child to sleep – it can't be done abruptly.

Do you read your reviews?

Not if somebody has told me

in advance that it isn't good. The only time I've ever learned anything from

a review was when John Lanchester wrote

a piece in the Guardian about my second novel, The Heather Blazing. He said

that, together with the previous novel, it represented a diptych about the

aftermath of Irish independence. I simply hadn't known that – and I loved the

grandeur of the word "diptych". I went around quite snooty for a few days,

thinking: "I wrote a diptych."

What advice would you give a young writer?Finish everything you start. Often, you don't know where you're going for a while; then halfway through, something comes and you know. If you abandon things, you never find that out.

What work of art would you most like to own?

Titian's Man With a

Glove. It's in the Louvre – right by the Mona Lisa. I'm probably the only

person who's looked at it in 100 years.

What's the biggest myth about writing?That there's any wildness attached to it. Writing tends to be very deliberate. A novelist could probably run a military campaign with some success. They could certainly run a country.

What are you writing now?

I'm close to finishing a novel. And I have a play [an adaptation of The Testament of Mary] opening on Broadway in about a month. There's a daily phone call from someone saying: "If we cut this sentence, would it break your heart?" Most of the time, I'm very good and say it wouldn't.

What's your greatest ambition?

To write better.

In short

Born: Enniscorthy, County Wexford, 1955

Career:

Has published nine novels and short story collections, including Brooklyn,

The Master and The

Testament of Mary; as well as various non-fiction works, the latest of which

– New

Ways to Kill Your Mother: Writers and Their Families – is out on 7 March.

His next novel will appear in the autumn.

Low point: "No lows and no highs – writing has just been a

gift."

No comments:

Post a Comment