Anxiety about narrative fiction's survival might be quietened by reflection on how poetry has reinvented itself for changing times

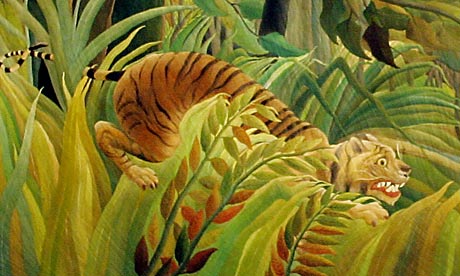

Fierce instinct for survival ... Detail from Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!) by Henri Rousseau. Photograph: Carl De Souza/AFP/Getty Images

Yesterday, at the Edinburgh International Book festival, China Miéville gave the final World Writers' Conference keynote speech on the future of the novel. The conversation between delegates ebbed and flowed afterwards but one of the most notable remarks came from Jackie Kay, who responded to what she perceived as an atmosphere of gloom about the novel's survival with bemusement. "Why do novelists so fear the death of the novel?" she asked. "Poets don't fear the death of the poem."

There is constant and loud debate about the death of the novel – Will Self was voicing his doubts about it only this week – but far less debate (though not none) about the death of the poem. The true distinction, however, is not between novels and poems, but between poems and storytelling. The novel is a specific but not fixed form of storytelling, in the same way as the romantic lyric, or the sonnet, is a form of poetry. The two deep patterns are story and poem.

There are two essential instincts in engaging with the world through language. The first is the cry of encounter linked to the desire to name; the second is the evaluation of options as a result of the encounter.

The Tyger is a poem by William Blake. Tiger! Tiger! is a story by Rudyard Kipling, introduced by a verse. The first doesn't tell a story but offers us a burning presence in the imagination: the second doesn't dwell on presence except in so far as it is an aspect of consequence. Consequence is vital. To take a very brief passage from Kipling:

"Because Purun Dass always limped". In stories there is always an implied "and then", and a "because". There is neither a 'then' nor a 'because' in Blake. No one reads a poem like Blake's to find out what happens in the last line. The end is the beginning.

There are various forms of narrative poem. We can deploy the old categories and talk of epic poems, discursive poems, and dramatic poems as well as lyrical poems, but there is something significant in what Edgar Allan Poe argued: that longer poems are essentially linked short poems, a series of flashes.

Full essay at The Guardian

There is constant and loud debate about the death of the novel – Will Self was voicing his doubts about it only this week – but far less debate (though not none) about the death of the poem. The true distinction, however, is not between novels and poems, but between poems and storytelling. The novel is a specific but not fixed form of storytelling, in the same way as the romantic lyric, or the sonnet, is a form of poetry. The two deep patterns are story and poem.

There are two essential instincts in engaging with the world through language. The first is the cry of encounter linked to the desire to name; the second is the evaluation of options as a result of the encounter.

The Tyger is a poem by William Blake. Tiger! Tiger! is a story by Rudyard Kipling, introduced by a verse. The first doesn't tell a story but offers us a burning presence in the imagination: the second doesn't dwell on presence except in so far as it is an aspect of consequence. Consequence is vital. To take a very brief passage from Kipling:

Buldeo was explaining how the tiger that had carried away Messua's son was a ghost-tiger, and his body was inhabited by the ghost of a wicked, old money-lender, who had died some years ago. "And I know that this is true," he said, "because Purun Dass always limped from the blow that he got in a riot when his account books were burned, and the tiger that I speak of he limps, too, for the tracks of his pads are unequal.

"Because Purun Dass always limped". In stories there is always an implied "and then", and a "because". There is neither a 'then' nor a 'because' in Blake. No one reads a poem like Blake's to find out what happens in the last line. The end is the beginning.

There are various forms of narrative poem. We can deploy the old categories and talk of epic poems, discursive poems, and dramatic poems as well as lyrical poems, but there is something significant in what Edgar Allan Poe argued: that longer poems are essentially linked short poems, a series of flashes.

Full essay at The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment