At the time of his death in a car crash aged 57, WG Sebald was widely regarded as one of the world's greatest writers. James Wood, Iain Sinclair, Robert Macfarlane and Will Self reflect on what his work means to them

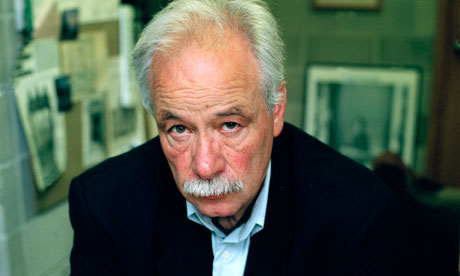

WG Sebald in his office at the University of East Anglia shortly before he died. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe for the Guardian

James Wood

When I first read WG Sebald's great work, The Emigrants, I kept forgetting whether the book was originally written in German or English. Sebald wrote in German, but lived most of his life in Britain, and it was clear that he worked over the English so that it amounted almost to a collaboration with his translator. Sebald's prose belongs, mysteriously, nowhere. The enigmatic patience of the sentences, the pedantic syntax, the peculiar antiquity of the diction, the strange recessed distance of the writing, in which everything seems milky and sub-aqueous, just beyond reach – all of this gives Sebald his particular flavour, so that sometimes it seems that we are reading not a particular writer but an emanation of literature.There's an undeniably bookish quality to Sebald's writing; despite his originality, some of his effects come from other writers. He takes his 19th-century Gothic diction from the Austrian writer Adalbert Stifter, and a fair amount of his obsessive extremism from the Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard. (Sebald mutes Bernhard's suicidal clamour.) The effect is strange – Sebald seems both real and artificial, both alive and dead. In the essay published here, for instance, the author seems to be telling us directly about the time he spent on the island of Saint-Pierre. Yet the self-conscious pedantry – "during which time I passed not a few hours sitting by the window"; "an island with a circumference of some two miles" – makes the author a little distant, and we begin to wonder if the essay is a true account or a literary concoction spun in the study.

As Sebald unfolds the story of Rousseau's tribulations ("a dozen years filled with fear and panic"), the essay seems, in its placeless antiquity, like one of Rousseau's own Reveries of a Solitary Walker, and suddenly it's not Rousseau's obsessive inability to stop thinking that is the theme, but Sebald's own obsessive inability ("the thoughts constantly brewing in his head like storm clouds"). In this way – and also, of course, through his use of photographs – Sebald was always asking us to reflect on how we access the past, how we rescue the dead, and how the writer performs that real, but necessarily fictional, reclamation.

More

No comments:

Post a Comment