As he awaits the British reviews of his translation of The Divine Comedy, Clive James talks to Robert McCrum about his illness, his marital split, TV criticism and his 'joking seriousness'

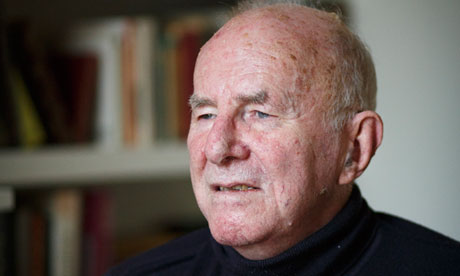

Clive James at 73. Photograph: Frantzesco Kangaris

"I'm told that I'm looking quite shiny," says Clive James, putting his best face on things with a vintage display of Anglo-Australian stoicism. It's an instinctive optimism that is what you'd expect, but still it is moving.

Almost everything in the life of this great literary polymath is edged with darkness. James now dwells in a kind of internal exile: from family, from good health and from convivial literary association, even from his own native land. His circumstances in old age – James is 73 – evoke a fate that Dante might plausibly have inflicted on a junior member of the damned in one of the less exacting circles of hell.

James's health has lately been so bad that, last year, he was obliged publicly to deny a viral rumour of his imminent demise. Two or three times, indeed, since falling ill on New Year's day in 2010, he has nearly died, but has somehow contrived (so far) to play the Comeback Kid. Perhaps he has found rejuvenation in the macabre satisfaction of reading premature rave obituaries from fans around the English-speaking world. If word of his death has been exaggerated, there's no question, on meeting him, that he's into injury time, with a nagging cough that punctuates our conversation.

"Essentially," he says, as we settle into the rather spartan living room of his two-up, two-down terraced house in Cambridge, "I've got the lot. Leukaemia is lurking, but it's in remission. The thing that rips up my chest is the emphysema. Plus I've got all kinds of little carcinomas." He points to the place on his right ear where a predatory oncologist has recently removed a threatening growth. "I'd love to see Australia again," he reflects. "But I can't go further than three weeks away from Addenbrooke's hospital, so that means I'm here in Cambridge."

In a recent, valedictory poem, "Holding Court", which describes his involuntary sequestration, he writes: "My wristband feels too loose around my wrist." In all other respects, he is tightly shackled to his fate.

Exiled from his homeland, where he has now become a much-loved grand old man of Australian letters, James is also exiled in Cambridge. His wife of 45 years, the Dante scholar Prue Shaw, kicked him out of the marital home last year on the disclosure of his long affair with a former model, Leanne Edelsten. This betrayal also devastated his two daughters, though it has ultimately brought them closer to their father. In "Holding Court", James writes ruefully that "retreating from the world, all I can do, is build a new world".

He is doing that this month in the only way he knows, and in the way he has always done – in print. With a grim appropriateness, his new book is an extraordinary verse-rendering – the fruit of many years' work – of Dante's The Divine Comedy. According to TS Eliot, this is the only book in the western tradition that surpasses Shakespeare. It is typical of James's chutzpah that he has not only tackled this Everest of translation, but has scrambled to the summit in triumph.

James reports that, in Australia, he has been getting "wonderful reviews, which is very gratifying". Now, he waits with some apprehension for the British critical response, knowing all too well that over the years he has been acclaimed as an entertainer but mercilessly criticised as the clown who wants to play Hamlet.

Flak is something he has had to deal with from the minute he decided to leave Kogarah, New South Wales. James comes from that remarkable generation of ambitious postwar Australians – other members are Robert Hughes and Germaine Greer – who felt they had to get out. "We all thought that the real action was overseas," he says. Any regrets about not going back? He has been burned too often by the Sydney media to answer that easily. "Let's just say, yes – and no," he replies. "Australia offers a wonderful life, but I've made my life here." Tellingly, he slips into the past tense to consider his career. "I didn't get a bad ride. I managed to square the circle."

Vivian Leopold James (he adopted "Clive" after Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara made his name seem girlish), born in 1939, has said that "the other big event of that year was the outbreak of the second world war". Challenged with this now, he laughs and says: "Dramatising myself is what I do." A prisoner of his childhood, as he puts it, he landed in England in the winter of 1962, having promised his Sydney friends he would be gone for just five years.

But then he went to university in Cambridge. James, slightly older than his fellow students, became a leader of the revels and discovered a taste for mixing erudition with performance. He has been showing off ever since.

More

Almost everything in the life of this great literary polymath is edged with darkness. James now dwells in a kind of internal exile: from family, from good health and from convivial literary association, even from his own native land. His circumstances in old age – James is 73 – evoke a fate that Dante might plausibly have inflicted on a junior member of the damned in one of the less exacting circles of hell.

James's health has lately been so bad that, last year, he was obliged publicly to deny a viral rumour of his imminent demise. Two or three times, indeed, since falling ill on New Year's day in 2010, he has nearly died, but has somehow contrived (so far) to play the Comeback Kid. Perhaps he has found rejuvenation in the macabre satisfaction of reading premature rave obituaries from fans around the English-speaking world. If word of his death has been exaggerated, there's no question, on meeting him, that he's into injury time, with a nagging cough that punctuates our conversation.

"Essentially," he says, as we settle into the rather spartan living room of his two-up, two-down terraced house in Cambridge, "I've got the lot. Leukaemia is lurking, but it's in remission. The thing that rips up my chest is the emphysema. Plus I've got all kinds of little carcinomas." He points to the place on his right ear where a predatory oncologist has recently removed a threatening growth. "I'd love to see Australia again," he reflects. "But I can't go further than three weeks away from Addenbrooke's hospital, so that means I'm here in Cambridge."

In a recent, valedictory poem, "Holding Court", which describes his involuntary sequestration, he writes: "My wristband feels too loose around my wrist." In all other respects, he is tightly shackled to his fate.

Exiled from his homeland, where he has now become a much-loved grand old man of Australian letters, James is also exiled in Cambridge. His wife of 45 years, the Dante scholar Prue Shaw, kicked him out of the marital home last year on the disclosure of his long affair with a former model, Leanne Edelsten. This betrayal also devastated his two daughters, though it has ultimately brought them closer to their father. In "Holding Court", James writes ruefully that "retreating from the world, all I can do, is build a new world".

He is doing that this month in the only way he knows, and in the way he has always done – in print. With a grim appropriateness, his new book is an extraordinary verse-rendering – the fruit of many years' work – of Dante's The Divine Comedy. According to TS Eliot, this is the only book in the western tradition that surpasses Shakespeare. It is typical of James's chutzpah that he has not only tackled this Everest of translation, but has scrambled to the summit in triumph.

James reports that, in Australia, he has been getting "wonderful reviews, which is very gratifying". Now, he waits with some apprehension for the British critical response, knowing all too well that over the years he has been acclaimed as an entertainer but mercilessly criticised as the clown who wants to play Hamlet.

Flak is something he has had to deal with from the minute he decided to leave Kogarah, New South Wales. James comes from that remarkable generation of ambitious postwar Australians – other members are Robert Hughes and Germaine Greer – who felt they had to get out. "We all thought that the real action was overseas," he says. Any regrets about not going back? He has been burned too often by the Sydney media to answer that easily. "Let's just say, yes – and no," he replies. "Australia offers a wonderful life, but I've made my life here." Tellingly, he slips into the past tense to consider his career. "I didn't get a bad ride. I managed to square the circle."

Vivian Leopold James (he adopted "Clive" after Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara made his name seem girlish), born in 1939, has said that "the other big event of that year was the outbreak of the second world war". Challenged with this now, he laughs and says: "Dramatising myself is what I do." A prisoner of his childhood, as he puts it, he landed in England in the winter of 1962, having promised his Sydney friends he would be gone for just five years.

But then he went to university in Cambridge. James, slightly older than his fellow students, became a leader of the revels and discovered a taste for mixing erudition with performance. He has been showing off ever since.

More

No comments:

Post a Comment