Tennessee Williams, F Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Cheever, Carver, Berryman… Six giants of American literature – and all addicted to alcohol. In an edited extract from her new book, The Trip to Echo Spring, Olivia Laing looks at the link between writers and the bottle

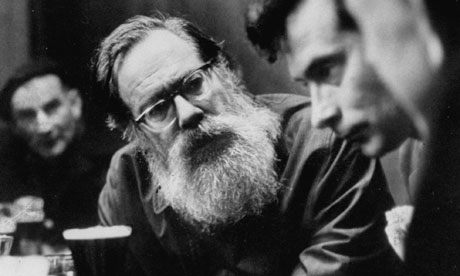

The poet John Berryman (bearded) shares beer and conversation with drinkers in a Dublin pub in 1967.

Five years later, in 1972, after several failed rounds of treatment for alcohol addiction, he took a train to the Washington Avenue bridge in St Paul and threw himself 100 feet into the Mississippi. His body was identified from a blank cheque found in his pocket and the name on his broken glasses. Photograph: Terrence Spencer/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image

In the small hours of 25 February 1983, the playwright Tennessee Williams died in his suite at the Elysée, a small, pleasant hotel on the outskirts of the Theatre District in New York City. He was 71: unhappy, a little underweight, addicted to drugs and alcohol and paranoid sometimes to the point of delirium. According to the coroner's report, he'd choked on the bell-shaped plastic cap of a bottle of eyedrops, which he was in the habit of placing on or under his tongue while he administered to his vision.

The next day, the New York Times ran an obituary claiming him as "the most important American playwright after Eugene O'Neill", though it had been two decades since his last successful play. It listed his three Pulitzer prizes, for A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Night of the Iguana, adding: "He wrote with deep sympathy and expansive humour about outcasts in our society. Though his images were often violent, he was a poet of the human heart."

The next day, the New York Times ran an obituary claiming him as "the most important American playwright after Eugene O'Neill", though it had been two decades since his last successful play. It listed his three Pulitzer prizes, for A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Night of the Iguana, adding: "He wrote with deep sympathy and expansive humour about outcasts in our society. Though his images were often violent, he was a poet of the human heart."

He was also a kind, generous, hard-working man, who rose at dawn almost every morning of his life, sitting down at his typewriter with a cup of black coffee to produce what would amount to well over 100 short stories and plays. At the same time, he was a lonely, depressed alcoholic who managed by degrees to isolate himself from almost everyone he loved. A sample entry from his diary in 1957 reads: "Two Scotches at bar. 3 drinks in morning. A daiquiri at Dirty Dick's, 3 glasses of red wine at lunch and 3 of wine at dinner. Also two seconals so far, and a green tranquillizer whose name I do not know and a yellow one I think is called reserpine or something like that" – an itemisation made more troubling by the fact that he was in rehab at the time.

Things got worse in 1963, when Williams's long-term partner Frank Merlo, nicknamed the Little Horse, died of lung cancer. After that, he was far gone and out, barely perpendicular against the current, buoyed on a diet of coffee, liquor, barbiturates and speed. Hardly any wonder he found speech difficult, or kept toppling over in bars, theatres and hotels. Each year he put on a new play, and each year it failed, rarely lasting a month before it closed.

Two years before he died, Williams was interviewed in the Paris Review. He talked about his work and the people he had known, and he touched too, a little disingenuously, on the role of alcohol in his life, saying: "O'Neill had a terrible problem with alcohol. Most writers do. American writers nearly all have problems with alcohol because there's a great deal of tension involved in writing, you know that. And it's all right up to a certain age, and then you begin to need a little nervous support that you get from drinking."

More

The next day, the New York Times ran an obituary claiming him as "the most important American playwright after Eugene O'Neill", though it had been two decades since his last successful play. It listed his three Pulitzer prizes, for A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Night of the Iguana, adding: "He wrote with deep sympathy and expansive humour about outcasts in our society. Though his images were often violent, he was a poet of the human heart."

The next day, the New York Times ran an obituary claiming him as "the most important American playwright after Eugene O'Neill", though it had been two decades since his last successful play. It listed his three Pulitzer prizes, for A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Night of the Iguana, adding: "He wrote with deep sympathy and expansive humour about outcasts in our society. Though his images were often violent, he was a poet of the human heart."He was also a kind, generous, hard-working man, who rose at dawn almost every morning of his life, sitting down at his typewriter with a cup of black coffee to produce what would amount to well over 100 short stories and plays. At the same time, he was a lonely, depressed alcoholic who managed by degrees to isolate himself from almost everyone he loved. A sample entry from his diary in 1957 reads: "Two Scotches at bar. 3 drinks in morning. A daiquiri at Dirty Dick's, 3 glasses of red wine at lunch and 3 of wine at dinner. Also two seconals so far, and a green tranquillizer whose name I do not know and a yellow one I think is called reserpine or something like that" – an itemisation made more troubling by the fact that he was in rehab at the time.

Things got worse in 1963, when Williams's long-term partner Frank Merlo, nicknamed the Little Horse, died of lung cancer. After that, he was far gone and out, barely perpendicular against the current, buoyed on a diet of coffee, liquor, barbiturates and speed. Hardly any wonder he found speech difficult, or kept toppling over in bars, theatres and hotels. Each year he put on a new play, and each year it failed, rarely lasting a month before it closed.

Two years before he died, Williams was interviewed in the Paris Review. He talked about his work and the people he had known, and he touched too, a little disingenuously, on the role of alcohol in his life, saying: "O'Neill had a terrible problem with alcohol. Most writers do. American writers nearly all have problems with alcohol because there's a great deal of tension involved in writing, you know that. And it's all right up to a certain age, and then you begin to need a little nervous support that you get from drinking."

More