Innocence – the first of Fitzgerald's four late novels – is as shrewd and calculating as its main characters are notl

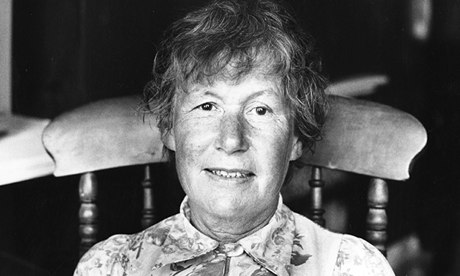

Invention and ambition … Penelope Fitzgerald. Photograph: Jane Bown

Penelope Fitzgerald liked to begin her late novels with quiet acts of indirection. The first sentence of The Blue Flower contains a disrupting double negative; The Beginning of Spring opens with a character leaving the very city where most of the book's action is going to take place. We are being put on our guard, politely warned not to take things for granted. But neither of these novels begins in as apparently wrong-footing a way as Innocence. Though the novel is to be set in Florence in 1955, its first chapter plants us back in mid-16th-century Italy, at the Villa Ricordanza, inhabited by the Ridolfis, a family of aristocratic midgets. The Ridolfis dote on their young daughter, and so practise many kindly deceptions to convince her that her genetic condition, far from being a handicap, is not even an aberration. She is surrounded only by those the same size as herself, and is never allowed to leave the villa to discover the truths of the outside world. She is also provided with a female companion, Gemma, a dwarf (as opposed to a midget), whom she pities, and then pities the more when a sudden spurt of growth occurs. Poor girl, about to become a giantess, a freak, and to have to face this fact … and so the daughter, who has "a compassionate heart", comes up with a solution for Gemma, as well-meaning in its intent as it is ghoulishly cruel in its actuality

After these first four pages, we suddenly jump four centuries to the modern world, by which time the descendants of that Ridolfi family have become normal-sized and are nowadays eccentric only in socially acceptable ways. So were we just being presented with a colourful backstory, an attention-grabbing anecdote from the guide book? Not at all. That genetic aberration of the Ridolfis may have been fixed over the succeeding centuries, but there are other family characteristics, less physical than moral, that have survived:

After these first four pages, we suddenly jump four centuries to the modern world, by which time the descendants of that Ridolfi family have become normal-sized and are nowadays eccentric only in socially acceptable ways. So were we just being presented with a colourful backstory, an attention-grabbing anecdote from the guide book? Not at all. That genetic aberration of the Ridolfis may have been fixed over the succeeding centuries, but there are other family characteristics, less physical than moral, that have survived:

"No more midgets among them now. Still a tendency towards rash decisions, perhaps, always intended to ensure other people's happiness, once and for all. It seems an odd characteristic to survive for so many years. Perhaps it won't do so for much longer."

More

After these first four pages, we suddenly jump four centuries to the modern world, by which time the descendants of that Ridolfi family have become normal-sized and are nowadays eccentric only in socially acceptable ways. So were we just being presented with a colourful backstory, an attention-grabbing anecdote from the guide book? Not at all. That genetic aberration of the Ridolfis may have been fixed over the succeeding centuries, but there are other family characteristics, less physical than moral, that have survived:

After these first four pages, we suddenly jump four centuries to the modern world, by which time the descendants of that Ridolfi family have become normal-sized and are nowadays eccentric only in socially acceptable ways. So were we just being presented with a colourful backstory, an attention-grabbing anecdote from the guide book? Not at all. That genetic aberration of the Ridolfis may have been fixed over the succeeding centuries, but there are other family characteristics, less physical than moral, that have survived:"No more midgets among them now. Still a tendency towards rash decisions, perhaps, always intended to ensure other people's happiness, once and for all. It seems an odd characteristic to survive for so many years. Perhaps it won't do so for much longer."

More

No comments:

Post a Comment