Books of the year: writers pick their favourites Photograph: guardian.co.uk

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Tobys Room Eghosa Imasuen's Fine Boys (Farafina Books, available on Kindle) is, simply put, a very good read. It is about middle-class life in 1990s Nigeria, boys coming of age amid the lure of violence and the pull of young love. It is moving, funny and emotionally true.

Eghosa Imasuen's Fine Boys (Farafina Books, available on Kindle) is, simply put, a very good read. It is about middle-class life in 1990s Nigeria, boys coming of age amid the lure of violence and the pull of young love. It is moving, funny and emotionally true.Pat Barker's Toby's Room (Hamish Hamilton) is magnificent; the characters have psychological depth, and she deals, in an honest, knowledgeable way with gender and art during the first world war. I finished it eagerly, wanting to know what happened next, and as I read, I was enjoying, marvelling and learning.

Simon Armitage

I've become a big fan of the short novel of late, something about the length of a day return from Leeds to London, so Denis Johnson's Train Dreams (Granta) was always going to appeal. Stark and terse, it's the story of 1920s lumber-man Robert Grainier, whose existence is consumed by America's uncontrollable expansion. He is pioneer, dreamer, everyman, and his life among the trees, forest fires and bawdy towns speaks both of paradise and apocalypse, all told with Johnson's maverick approach to grammar and structure.

Often overlooked as a poet now, Stephen Spender wrote over a million words of journal entries. The index of New Selected Journals: 1939-95 (Faber) reads like a cross between Who's Who and a London restaurant guide, but name-dropping and menu choices aside, some of his later writings as body and spirit begin to fail are touching and humane.

In Meme (University of Iowa Press) Susan Wheeler intercuts fragmentary poetic reflection with snatches of vernacular phrasing ("wait I'm not done fucking yet") to explore broken relationships – parental, romantic and with the self. The overall effect is dazzling, upsetting at times, and like nothing I've read before.

Diana Athill

Diana Athill

Kathleen Jamie, Sightlines There's been an embarrassment of riches this year, but here are two to be treasured and reread. In Tom Lubbock's Until Further Notice, I Am Alive (Granta) he regrets that no "teaching how to die" is available. His own awe-inspiring book is just that. It is unforgettable and profoundly valuable. While Kathleen Jamie's Sightlines (Sort Of Books), a collection of brilliant and enticing essays about natural phenomena, tingles with life. John Berger called her a "sorceress", and so she is.William Boyd

Two tremendous new collections by two of my favourite poets enlivened this year's reading. Jamie McKendrick's Out There (Faber) displays all his prodigious strengths – a roving, quirky erudition, spectacularly precise observation and a beguiling, shrewd wit. And Christopher Reid, after the triumph of The Song of Lunch shows in Nonsense (Faber) that he is the modern master of the long narrative poem – at once wryly amusing and moving. Both these poets superbly exemplify Coleridge's definition of the form: "The best words in their best order."Donald Rayfield's Edge of Empires (Reaktion Press) is a wonderful history of Georgia, lifting the lid on that country's torrid, rambunctious past (and present). Impeccably researched, limpidly written and full of insight.

AS Byatt

Lawrence Norfolk, John Saturnall's Feast There were four novels I confidently expected to see on the Man Booker lists, or even as the winner. Philip Hensher's Scenes from Early Life (Fourth Estate) is an extraordinary feat of imagination, telling of the birth of Bangladesh in colour and light. Lawrence Norfolk's John Saturnall's Feast (Bloomsbury) is a brilliant, erudite tale of cookery and witchcraft in 1681.

There were four novels I confidently expected to see on the Man Booker lists, or even as the winner. Philip Hensher's Scenes from Early Life (Fourth Estate) is an extraordinary feat of imagination, telling of the birth of Bangladesh in colour and light. Lawrence Norfolk's John Saturnall's Feast (Bloomsbury) is a brilliant, erudite tale of cookery and witchcraft in 1681.Patrick Flanery's Absolution (Atlantic) is a wonderfully constructed and gripping novel about betrayal and shadows in South Africa. Grace McCleen's The Land of Decoration (Chatto & Windus) is both sinister and sharply intriguing, with a completely convincing 11-year-old narrator caught in fundamentalism, school persecution and the edge of the miraculous. None of them resembles anything else. The fact that none of them was on the Man Booker lists may simply indicate that we are going through an extraordinarily various and imaginative period for British fiction.

Rachel Cusk

The best book I read this year was Karl Ove Knausgaard's A Death in the Family (Harvill Secker); in fact, I continue to read parts of it at regular intervals. It is both an account of mid-life and of childhood remembered from mid-life, with the death of the author's father bringing these two periods into relation. It is what might be called a work of extreme autobiography, and is full of artistic, moral and technical daring. Knausgaard's commentaries on painting, particularly on Rembrandt's self-portraits, are very beautiful. The idea that a self-portrait arises out of an abandonment of the notion of solace underpins Knausgaard's own self-portrait; yet solace is precisely what it offers.Richard Ford

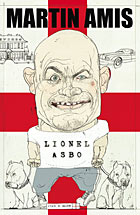

Lionel Asbo Photograph: Cape Lionel Asbo (Jonathan Cape) by Martin Amis – it'd be quite enough for this terrific, boisterous novel just to piss off all the rumpled grumpies and tight-knickered critics who like to tell us what's funny and what's serious (they're almost always wrong). But this novel manages to be both funny and serious, and (as always with Amis) to be very, very on-the-money about the culture – and not just British culture – and along the way to get at what we're uncomfortably thinking and don't want others to know we're thinking. Satire? Fairy tale? Send up? There's not enough of it for me. Amis does the reader a brilliant, generous (and cathartic) favour.

Lionel Asbo (Jonathan Cape) by Martin Amis – it'd be quite enough for this terrific, boisterous novel just to piss off all the rumpled grumpies and tight-knickered critics who like to tell us what's funny and what's serious (they're almost always wrong). But this novel manages to be both funny and serious, and (as always with Amis) to be very, very on-the-money about the culture – and not just British culture – and along the way to get at what we're uncomfortably thinking and don't want others to know we're thinking. Satire? Fairy tale? Send up? There's not enough of it for me. Amis does the reader a brilliant, generous (and cathartic) favour.Philip Larkin: Letters to Monica edited by Anthony Thwaite (Faber) – I don't ordinarily like reading people's letters. Usually, too many punches get knowingly, smirkingly pulled. Larkin, of course, is different: hilarious, pathetic, niggardly, mischievous, baiting, amusingly domestic, insincere, placating and occasionally loving, and brilliant, incisive and true; he's us, in our best and worst selves – written better than we could write it. Why else would a critic argue that he's the "best-loved poet of the past 100 years"? In these letters, no less than in his poems, he stands rather nakedly before us – only this time with a damp dish towel over his wrist, the room gone a bit too cold, thinking about listening to the radio from bed.

More at The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment