Michael Gove plans to remove Of Mice and Men and To Kill a Mockingbird from school reading lists, in favour of Dickens and Austen. It's certainly a mistake to abandon American literature – but which US classics deserve a place in our classrooms?

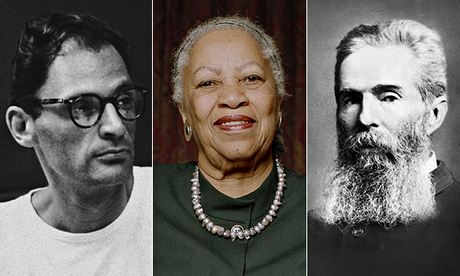

Arthur Miller, Toni Morrison, Herman Melville. Photograph: Getty, Eamonn McCabe

Cynics will, of course, hear an echo of President Esposito in Woody Allen's Bananas. "From this day on, the official language of San Marcos will be Swedish." From now on, decrees Michael Gove, the official literature of England will be English literature.

Gove has harped on this chauvinistic string for some time now. As he told his party conference, on assuming office: "The great tradition of our literature – Dryden, Pope, Swift, Byron, Keats, Shelley, Austen, Dickens and Hardy – should be at the heart of school life." (His indifference to Scottish literature is odd for someone who went to an Aberdeen grammar school.)

He has expressed a personal distaste for John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men. Some 90% of exam candidates answer on it, we're told. Gove clearly sees it as contaminated with the ideological prejudices of the left-leaning teaching profession. It's a novella set in a recession, about two migrants on zero-hours contracts. In short, it's a work of fiction propagandising for Roosevelt's New Deal and "social security" – those welfare dragons Iain Duncan Smith is endeavouring to slay. To Kill a Mockingbird, another title on the Gove blacklist, makes a collateral fictional push for the 1964 American civil rights bill. Arthur Miller's Crucible (it too will go) is an allegory about McCarthyism.

These texts are, Gove thinks (quite rightly), loaded, and he doesn't think the ideological baggage they're carrying is entirely relevant for British schoolchildren. It's an honest opinion.

My own honest opinion is that American literature should be as prominent on the British syllabus as British literature is on the American syllabus. And what should be highlighted in the texts for the British classroom is what William Carlos Williams called that unique "American grain". What, then, would be the best 10 prescribed works?

More

Gove has harped on this chauvinistic string for some time now. As he told his party conference, on assuming office: "The great tradition of our literature – Dryden, Pope, Swift, Byron, Keats, Shelley, Austen, Dickens and Hardy – should be at the heart of school life." (His indifference to Scottish literature is odd for someone who went to an Aberdeen grammar school.)

He has expressed a personal distaste for John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men. Some 90% of exam candidates answer on it, we're told. Gove clearly sees it as contaminated with the ideological prejudices of the left-leaning teaching profession. It's a novella set in a recession, about two migrants on zero-hours contracts. In short, it's a work of fiction propagandising for Roosevelt's New Deal and "social security" – those welfare dragons Iain Duncan Smith is endeavouring to slay. To Kill a Mockingbird, another title on the Gove blacklist, makes a collateral fictional push for the 1964 American civil rights bill. Arthur Miller's Crucible (it too will go) is an allegory about McCarthyism.

These texts are, Gove thinks (quite rightly), loaded, and he doesn't think the ideological baggage they're carrying is entirely relevant for British schoolchildren. It's an honest opinion.

My own honest opinion is that American literature should be as prominent on the British syllabus as British literature is on the American syllabus. And what should be highlighted in the texts for the British classroom is what William Carlos Williams called that unique "American grain". What, then, would be the best 10 prescribed works?

More

No comments:

Post a Comment