The humiliations, the parties, the failures of analysis – Pankaj Mishra on Salman Rushdie's memoir

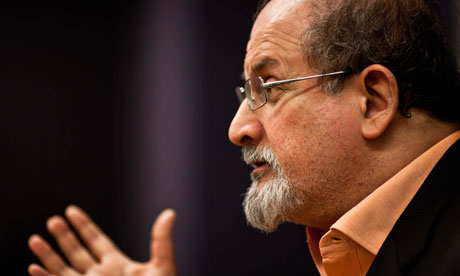

Rushdie: 'a Cassandra for his own time'. Photograph: Sipa Press/Rex Features

"Politics and literature," Salman Rushdie wrote in 1984, in what now seems an innocent time, "do mix, are inextricably mixed, and that … mixture has consequences." Criticising George Orwell for having advocated political quietism to writers, Rushdie asserted that "we are all irradiated by history, we are radioactive with history and politics" and that, "in this world without quiet corners, there can be no easy escapes from history, from hullabaloo, from terrible, unquiet fuss.

Five years later, his novel The Satanic Verses would be abruptly inserted into a series of ongoing domestic and international confrontations in the west and Muslim countries. Sentenced to death by an Iranian theocrat, Rushdie himself would embody the perils of mixing politics and literature in an interconnected and volatile world, where, as Paul Valéry once warned, "nothing can ever happen again without the whole world's taking a hand" and where "no one will ever be able to predict or circumscribe the almost immediate consequences of any undertaking whatever."

Five years later, his novel The Satanic Verses would be abruptly inserted into a series of ongoing domestic and international confrontations in the west and Muslim countries. Sentenced to death by an Iranian theocrat, Rushdie himself would embody the perils of mixing politics and literature in an interconnected and volatile world, where, as Paul Valéry once warned, "nothing can ever happen again without the whole world's taking a hand" and where "no one will ever be able to predict or circumscribe the almost immediate consequences of any undertaking whatever."

In his new memoir Joseph Anton, which describes his life in hiding for more than a decade, Rushdie claims that The Satanic Verses was his "least political book". It was "an artistic engagement with the phenomenon of revelation", albeit from the perspective of an "unbeliever", but "a proper one nonetheless. How could that be thought offensive?" But then authorial intentions barely seemed to matter to readers bringing to the book their own particular backgrounds, worldviews and prejudices.

No one among Rushdie's early readers in Europe and America seems to have suspected that parts of the novel constituted, as Eliot Weinberger wrote in 1989, an "all-out parodic assault on the basic tenets of Islam". A pre-publication review in the Indian newsweekly India Today revealed that Rushdie had irreverently rewritten the life of the Prophet, the paradigmatic figure of virtue for all Muslims, naming him Mahound, the term used to identify him as a devil in medieval Christian caricature, and placing his 12 wives in a brothel. Rushdie claimed in the accompanying interview that the image out of which his book grew was of the Prophet "going to the mountain and not being able to tell the difference between the angel and the devil."

Full review at The Guardian

Five years later, his novel The Satanic Verses would be abruptly inserted into a series of ongoing domestic and international confrontations in the west and Muslim countries. Sentenced to death by an Iranian theocrat, Rushdie himself would embody the perils of mixing politics and literature in an interconnected and volatile world, where, as Paul Valéry once warned, "nothing can ever happen again without the whole world's taking a hand" and where "no one will ever be able to predict or circumscribe the almost immediate consequences of any undertaking whatever."

Five years later, his novel The Satanic Verses would be abruptly inserted into a series of ongoing domestic and international confrontations in the west and Muslim countries. Sentenced to death by an Iranian theocrat, Rushdie himself would embody the perils of mixing politics and literature in an interconnected and volatile world, where, as Paul Valéry once warned, "nothing can ever happen again without the whole world's taking a hand" and where "no one will ever be able to predict or circumscribe the almost immediate consequences of any undertaking whatever."In his new memoir Joseph Anton, which describes his life in hiding for more than a decade, Rushdie claims that The Satanic Verses was his "least political book". It was "an artistic engagement with the phenomenon of revelation", albeit from the perspective of an "unbeliever", but "a proper one nonetheless. How could that be thought offensive?" But then authorial intentions barely seemed to matter to readers bringing to the book their own particular backgrounds, worldviews and prejudices.

No one among Rushdie's early readers in Europe and America seems to have suspected that parts of the novel constituted, as Eliot Weinberger wrote in 1989, an "all-out parodic assault on the basic tenets of Islam". A pre-publication review in the Indian newsweekly India Today revealed that Rushdie had irreverently rewritten the life of the Prophet, the paradigmatic figure of virtue for all Muslims, naming him Mahound, the term used to identify him as a devil in medieval Christian caricature, and placing his 12 wives in a brothel. Rushdie claimed in the accompanying interview that the image out of which his book grew was of the Prophet "going to the mountain and not being able to tell the difference between the angel and the devil."

Full review at The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment