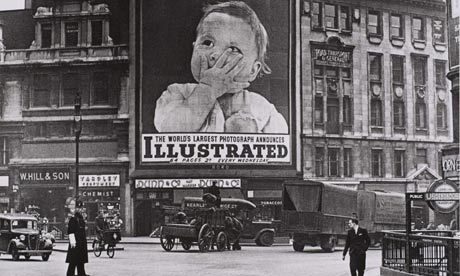

'The streets were excitingly busy but not uncomfortably so' … Near Monument Station, London 1938, from Tate Britain's Another London. Photograph: Wolfgang Suschitzky

Everyone has his or her own London, its boundaries defined by the individual's class and income. Mine, in the late 1920s, when I first met it as a child visiting from the country, consisted of the shop in Oxford Street where my shoes came from, which was called Daniel Neal's; the zoo; and Peter Pan's Never Never Land. During the 30s, it expanded rapidly, though Oxford Street remained central to it because of those stately emporia John Lewis, Marshall & Snelgrove and Debenham & Freebody (or was it Frebody? It was not like the modern Debenhams, being the one we shopped at least often because it was so expensive). My mother thought Selfridges vulgar. At that time, Bayswater and Kensington came into existence, but Bloomsbury, Hampstead and Chelsea were hardly even names. The streets in my London were excitingly busy but not uncomfortably so. If you drove along a street and saw a friend walking on the pavement, you could pull over and have a gossip. Everyone going by would be wearing a hat, and the men's hats would often be bowlers.

I began living in London 70 years ago, but my version of it is still quite small, its borders being roughly the Thames to the south, the North Circular to the north, Islington to the east (with a recent bulge to take in Shoreditch) and Hammersmith to the west. Of course, I have set foot in exotic parts such as Richmond and Kew, but not very often; and now I have ventured as far as Highgate, but old age prevents me from exploring the fascinating vistas stretching to the north. The most obvious way in which this version has changed since I first knew it is that it has become much more crowded. When I lived in Chelsea in the late 50s and early 60s, our street was a designated "play street", so the only cars in it were those of our neighbours, which is hardly imaginable nowadays. Waiting in King's Road for a number 11 bus, one naturally saw cars going by, but not in an unbroken stream.

Remembering the shops there, and in Fulham Road, Sloane Street, Brompton Road, and even more in the West End, makes me realise another change: London has lost its claim to elegance. Those parts of it that used to give an impression of elegance now simply look expensive in a way that suggests quite loudly that Expensiveness Is Best. Damien Hirst's diamond-coated skull epitomises this mood.

Before the war, the more prosperous inhabitants of my London took it for granted that a house should be kept spick and span: a front door received three (sometimes more) coats of paint, and the whole facade was probably done over about every three years. The war put an end to that, and when it ended the whole city had become pretty drab, even apart from the bomb damage. By the 60s, it had revived – I remember the pleasure of seeing a young man on a ladder applying real gold leaf, inch by inch, to the wrought iron of a gate into the Regent's Park rose garden. Recently, in spite of the huge amount of new building that sometimes makes it hard to recognise a once-familiar neighbourhood, I have begun to notice drabness creeping back – flaking stucco here, damaged paintwork there – and no doubt "austerity" will soon make it worse, so that our overcrowded, polluted city will become shabby again, except for the parts of it inhabited by those foreigners who can afford to live where natives who are not bankers can't.

But London will continue to be an easy and pleasant city to live in, given that one has a job, because it is so elastic: if people find it impossible to afford to live in one part of it, they shift to another. It has always been like that. And the part they shift to – this is the secret of London's charm – will soon become their village, because it's impossible for a city so vast not to break up into manageable units. There must have been a time a long way back in history when London felt like One Place, but gradually, while still knowing itself to be London, it became a conglomeration of villages, each with its own centre and character. It is not just a matter of where the money is; more, perhaps, of what was there before London swallowed it – buried villages, little towns, sometimes even farms, stubbornly continuing to make their ghostly presences felt.

I began living in London 70 years ago, but my version of it is still quite small, its borders being roughly the Thames to the south, the North Circular to the north, Islington to the east (with a recent bulge to take in Shoreditch) and Hammersmith to the west. Of course, I have set foot in exotic parts such as Richmond and Kew, but not very often; and now I have ventured as far as Highgate, but old age prevents me from exploring the fascinating vistas stretching to the north. The most obvious way in which this version has changed since I first knew it is that it has become much more crowded. When I lived in Chelsea in the late 50s and early 60s, our street was a designated "play street", so the only cars in it were those of our neighbours, which is hardly imaginable nowadays. Waiting in King's Road for a number 11 bus, one naturally saw cars going by, but not in an unbroken stream.

Remembering the shops there, and in Fulham Road, Sloane Street, Brompton Road, and even more in the West End, makes me realise another change: London has lost its claim to elegance. Those parts of it that used to give an impression of elegance now simply look expensive in a way that suggests quite loudly that Expensiveness Is Best. Damien Hirst's diamond-coated skull epitomises this mood.

Before the war, the more prosperous inhabitants of my London took it for granted that a house should be kept spick and span: a front door received three (sometimes more) coats of paint, and the whole facade was probably done over about every three years. The war put an end to that, and when it ended the whole city had become pretty drab, even apart from the bomb damage. By the 60s, it had revived – I remember the pleasure of seeing a young man on a ladder applying real gold leaf, inch by inch, to the wrought iron of a gate into the Regent's Park rose garden. Recently, in spite of the huge amount of new building that sometimes makes it hard to recognise a once-familiar neighbourhood, I have begun to notice drabness creeping back – flaking stucco here, damaged paintwork there – and no doubt "austerity" will soon make it worse, so that our overcrowded, polluted city will become shabby again, except for the parts of it inhabited by those foreigners who can afford to live where natives who are not bankers can't.

But London will continue to be an easy and pleasant city to live in, given that one has a job, because it is so elastic: if people find it impossible to afford to live in one part of it, they shift to another. It has always been like that. And the part they shift to – this is the secret of London's charm – will soon become their village, because it's impossible for a city so vast not to break up into manageable units. There must have been a time a long way back in history when London felt like One Place, but gradually, while still knowing itself to be London, it became a conglomeration of villages, each with its own centre and character. It is not just a matter of where the money is; more, perhaps, of what was there before London swallowed it – buried villages, little towns, sometimes even farms, stubbornly continuing to make their ghostly presences felt.

No comments:

Post a Comment